Review written by the author, Costas Taktsis, on Lydia Gravani's Paintings presented at the Skoufa 4 Gallery, on January 22, 1987.

"All the magic of the big city as seen above far into the night. The darkened expanse torn as under by a food-lit torrent. You can guess the spindle-like coming - and - going movement of rushing cars; pulsations of a live body. One needs to have a great wealth of emotional and spiritual maturity to achieve this quality of being able to become one with the lives of others, without falling into the deadly sin of hubris by visualizing them in the form of an abstract concept, but on the contrary to feel each one as separate entity. I do feel Lydia Gravani is decidedly endowed with this emotional and spiritual maturity and I also have the feeling that even if this were not actually part of her intentions it nevertheless springs forth from within these paintings with unintended candidness."

Costas Taktsis

author of "The Third Wedding"

Review written by one of the foremost art critics Mme Dora Eliopoulou-Rogan in the influential daily paper "Kathimerini" on January 22, 1987, on Lydia Gravani's Paintings presented at the Skoufa 4 Gallery.

"It is primarily the world of the night that has inspired the artist and, to be more specific, the atmosphere prevailing during the night. An atmosphere occupying a place in the artist's life and which incites connotations in the mind of the onlooker thanks to the painter's brush. This cosmogonic impact is at its apex in the work entitled "Night landscape". Actually we are confronted with a phantasmagoria of colours harmoniously laid out on the surface of the canvas. In fact it is an achievement considering that the composition is based directly to the highest possible degree on the sensation springing from the colours. A sensation equally related with the mobility engendered by the colours in the painting. The latter as a result of these characteristics acquires a third dimensional quality or even better a sphericity which gives rise to a sense of depth, as well as of projection in space. It has a magnetizing effect as we gaze at it while at the same time captivating our spirituality unhindered by all diversive factors. An intertwining of light which finds its expression in terms of colour. A translucent web floating in the universe. A phosphorescent ethereal coalescence of matter which draws in its track something essential from among the secrets of the creation of the cosmos and of a metaphysical sense of nature.

However, the general impression conveyed by this painting exhibition is one of an explosive work, not simply from the point of view of subject matter, but also from aspect of creative urge with which the artist has deciphered memories, life experiences and impressions. We are faced with a passion which based on an authentic, a genuine and therefore unique sensitiveness evokes in the onlooker similarly personal situations, feelings and event. Suggestive, enigmatic and especially stimulating, these works are a reflection of man's adventure. A reality as seen and experienced by the painter within the framework of an intense spirituality and ebullient insight.

One of the paintings marked by astonishing intensity is that which portrays a woman lying on her bed whose breathing and even her skin exhale the sense of a summer early afternoon. Owing to this woman and to the way with which the painters portrays her, we are in a position to grasp the feeling of timelessness and of the inner urges exuded during these hours."

Mme Dora Eliopoulou-Rogan

Review written by J. Moralis, Athens, February 4 1999.

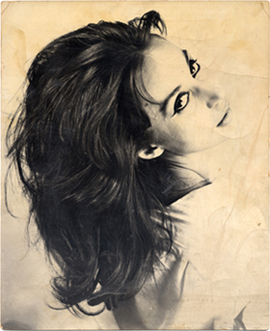

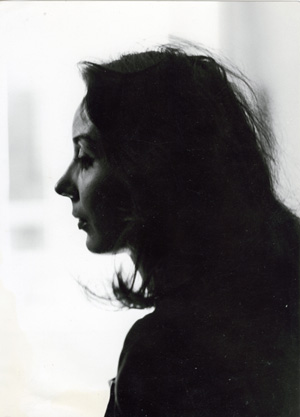

When Lydia Gravanis told me a few years ago that she wished to enroll in the Athens School of Fine Arts I didn’t think she actually meant it. Was it possible that this rebellious, impulsive woman was asking to submit to the discipline of instruction in order to learn? Learn what?

Yet, when she passed her entrance exams and joined my studio, she devoted herself to her work and resolutely handled the daily challenges of her studies, wanting to learn - as best as she could, the language of the art through which she chose to express herself. Her work is dreamlike, often violent and raw but honest and straightforward, without refinements and compromises. It’s a pity she left us so early.

J. Moralis

Review written by M. Z. Kopidakis. Darkness Visible.

Welcoming Gregorios Xenopoulos upon his election to the Academy of Athens, Pavlos Nirvanas made this flattering yet perceptive remark: “Dear colleague, I have read all your writings and I never suffered a dull moment!” All things considered, all of us who were friends or acquaintances of Lydia Gravanis could likewise assert that we never felt bored or uncomfortable while listening to her wide ranging comments, her well thought out views and poignant remarks regarding art scene personalities, current events and trends, as well as her thoughts on life and existence in general. Lydia was gifted, interesting and charming.

In her youth, swept away by the excruciating yet joyous fire that burned inside her -the fire of artistic expression, she was enchanted by the theater, the art which is put to the test on a daily basis and seeks immediate reciprocation in the audience’s applause. When her star started to shine she left the stage and turned to the fine arts, which require, much like writing, a different way of life: discipline, contemplation and solitude.

The work that Lydia bequeathed to future generations reflects her exuberant personality, multifaceted talent and audacious spirit, which mocked hypocrisy, obsolete social conventions and conformity head on. With a feverish pace, as if she could somehow foretell her untimely passing, she experimented with various materials showing special preference for oils, explored fields bordering painting, continued to serve the theater designing costumes and stage sets, and adopted many styles before settling in her first great love, the wild central European expressionism that better suited her uncompromising temperament, without succumbing to the safety of a single theme. The bee, this epitome of eclecticism in nature, does not limit itself to thyme, however fragrant it might be.

The dark ages in which men exerted absolute dominance on society, language and the arts forced women into silence and timidity. Patriarchy favored the glorification of the youthful and harmonious female body, but discouraged the representation of the male one in its entirety, that is entirely nude, especially if the artist who wanted to depict the most sensitive part, the male genitalia, was a woman. In the 1970s, Sylvia Sleigh, in such paintings as Philip Golub Reclining (1971) and The Turkish Bath (1973), reversed an age-old convention: instead of men gazing at the female nude, it was women who scrutinized the nude male body. Adopting such a feminist perspective, Lydia stood siccis oculis and rendered the roughness of the male nude along with the unexpected modesty that seizes a man’s body when confronted by woman’s unrelenting gaze.

Flowers are archetypal symbols of purity and sensuality, youth and inevitable decay, and as such they fall under the broader theme of vanitas. Lydia’s watercolor series of flowers may echo the work of Georgia O’ Keefe (1887-1986), the avant-garde American painter whose single flower closeups interpreted as alluding to the vulva scandalized the public in the 1920s. Not simple displays of virtuosity, Lydia’s flowers are subject to multiple interpretations.

The night was first extolled by the poets, from Aeschylus and Euripides (Electra 54, ὦ νὺξ μέλαινα, χρυσέων ἄστρων τροφέ - oh, black night, you who nurse the golden stars) to Novalis and Andreas Embirikos (“Many times at night.”) Composers such as Mozart, Chopin, Schumann and Debussy dedicated their most passionate compositions, the nocturnes, to the night. Nightscape painting was taken on by many artists including such towering figures as Giotto, James Abbott McNeill Whistler, Vincent van Gogh, René Magritte, Giorgio de Chirico and Edward Hopper. Black, the queen of colors, discourages even the daring.

The allure of genuine artistic expression, whether in literature or the fine arts, is not solely based on words or actions but also on the free associations triggered by them. Thus in Nightscape (1987, oil on canvas) for example, which in my opinion constitutes the pinnacle of Lydia Gravanis’s nightscape painting, she managed somehow to remind me of the magnificent visual and aural image of the Mt. Aetna volcano immortalized by Pindar in Pythian 1 [21]: “From Mt. Aetna’s inmost caves belch forth the purest streams of unapproachable fire. In the daytime her rivers roll out a fiery flood of smoke, while in the darkness of night the crimson flame hurls rocks down to the deep plain of the sea with a crashing roar. That monster shoots up the most terrible jets of fire; it is a marvelous wonder to see…”

Lydia Gravanis passed unexpectedly at the height of her creative powers leaving her relatives and friends in tears. However, she left future generations a body of work, which time, this infallible arbiter, and contemplative sensitivity will increasingly appreciate its value. This work reveals that the artist joined the ranks of the third wave of militant feminism that rejected the sexual, social and political enfranchisement of women. One of her works, a diptych composition with four women (1983, oil on canvas) bears the ironic title The Female Issue. Lydia fought for women’s social emancipation and emotional liberation, yet she treasured femininity as a precious gift that keeps women bound to earthly matters and reconciles them with pain, while allowing them to passionately and unreservedly fall in love. A female nude of hers (an acrylic from 1985) entitled The Origin of Memory and obviously referring to Gustave Courbet’s L’ Origine du Monde (1866) is not an extreme example of the objectification of women but a lyrical ode to that body part which is both ‘respected and feared’ (ἀιδοῖόν τε δεινόν τε) to paraphrase the verse spoken by Helen of Troy in Teichoscopia (Iliad, ΙΙΙ, 172 αἰδοῖός τε μοί ἐσσι φίλε ἑκυρὲ, δεινός τέ.)